Wooden skyscrapers could be the future of cities around the world

The development of engineered timber could herald a new era of eco-friendly ‘plyscrapers’. Christchurch welcomed its first multistorey timber structure this year, there are plans for Vancouver, and the talk is China could follow.

When American engineer William Le Baron Jenney designed the world’s first skyscraper in Chicago in 1884, no one believed in his unconventional technologies. His lightweight steel frame relieved a structure of its heavy masonry shackles, enabling it to soar to new heights. Perplexed by this trade-in of solid brick for a spindly steel skeleton, Chicago inspectors paused the construction of the Home Insurance Building until they were certain it was structurally sound.

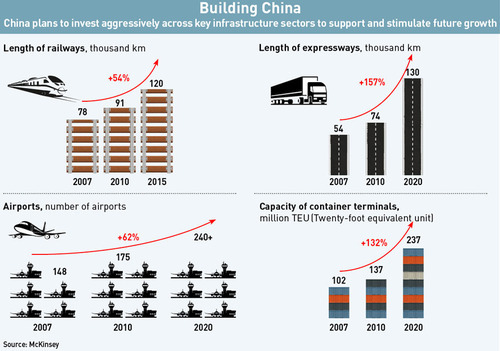

Of course, Jenney’s revolutionary edifice provided a blueprint for city skylines across the world. By 2011, China was reckoned to be topping off a new skyscraper (500ft or taller) every five days, reaching a total of 800 by 2016. Toronto, now North America’s fourth largest city, currently has 130 high-rise construction projects under way.

Chicago’s Home Insurance Building, widely considered to be the world’s first modern skyscraper. Photograph: Chicago History Museum/Getty Images

As a result, buildings are slowly choking the atmosphere. In Britain, where the construction industry accounts for almost7% of the economy (including 10% of total employment),47% of greenhouse gas emissions are generated from buildings, while 10% of CO2 emissions come from construction materials. Furthermore, 20% of the materials used on the average building site end up in a skip.

So just as Jenney’s steel-frame solved the issue of the dense, stunted buildings in the 19th century, architects and engineers are now seeking new ways of building taller and faster without having such a drastic impact on the environment. And that has seen them revisit the most basic building material of them all: wood.

Although wood in its raw form could not compete with Jenney’s steel-frame wonder, a type of super-plywood has been developed to step up to the challenge. By gluing layers of low-grade softwood together to create timber panels, today’s “engineered timber” is more akin to Ikea flat-packed furniture than traditional sawn lumber, and offers the prospect of a new era of eco-friendly “plyscrapers”.

For Vancouver-based architect Michael Green, the sky is the limit for wooden buildings. While nearing completion of the University of Northern British Columbia’s Wood Innovation and Design Centre in Prince George, Green’s practice, MGA, has also drawn up plans for a 30-storey, sun-grown tower for downtown Vancouver.

If built, Green’s vision would be easily the world’s tallest wooden building, soaring past the current contenders – London’s Stadthaus at nine storeys, and the 10-storey Forte Building in Melbourne. But that’s not the main motivation, according to MGA associate Carla Smith. “To be honest, it’s not like we really care about being the tallest,” she says. “We really do see a wooden future for cities, and our aim is to get others to jump on board too.”

The Nelson Marlborough Institute of Technology arts and media building under construction in Nelson, New Zealand

Green is giving away his hefty, 200-page instruction manual, The Case for Tall Wood Buildings, free of charge. He hopes it will inspire architects and engineers to branch out beyond their concrete and steel confinements, and embrace a material that sequesters carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, holding it captive during its growth and lifetime in a structure – one tonne of CO2 per cubic metre of wood. To put that in context, while a 20-storey wooden building sequesters about 3,100 tonnes of carbon, the equivalent-sized concrete building pumps out 1,200 tonnes. That net difference of 4,300 tonnes is the equivalent of removing 900 cars from the city for a year.

But while timber advocates such as Green hope to to sow the seeds of change in the minds of policymakers worldwide, building regulations still put a low-rise lid on the height of timber buildings. This is based on wood’s historic reputation as kindling for a great city fire: in London, Chicago and San Francisco (to name just a few), roaring fires have ravaged city streets, wiping out great swathes of grand architecture and razing urban history to the ground. But while the classic timber-framed city of 1870s Chicago was gone in an instant, today’s engineered timber develops a protective charring layer that maintains structural integrity and burns very predictably – unlike steel, which warps under the intense heat.

The rigidity of mass timber panels has tended to restrict architects to a “house of cards” design, whereby panels are slotted together and stacked on top of one another in repetitive patterns. But new innovations are coming thick and fast: theUSDA recently announced a $2m investment for wood innovation, and in the previously scorched city of Chicago, mega-firm Skidmore, Owings and Merrillpublished a study that re-imagines the 42-storey Dewitt Chestnut apartment block as a timber tower. In Europe, a 14-storey wooden building is currently under construction in Bergen, Norway, with another eight-storey structure on its way up in Dornbirn, Austria – the prototype for a 20-storey plyscraper designed by the global engineering firm Arup.

The finished NMIT arts and media building

One other important breakthrough came in British Columbia, a Canadian province half-covered in forest. Since 1996, more than 16m hectares have been destroyed by North America’s native mountain pine beetle, which releases a blue-staining fungus into the wood, halting the flow of nutrients and water and the killing the tree.

The province faced the prospect of billions of these dead lodgepole pinestriggering a huge release of carbon dioxide – until a means of using this undesirable blue-stained lumber for building was realised. British Columbia promotes its use through the Wood First Act, passed in 2009, which requires all new, publicly financed construction projects to first consider wood as the primary building material.

The most prominent example is Vancouver’s 2010 Winter Olympic ice rink, the Richmond Oval, which features massive glued-laminated timber arches of beetle-ravaged wood. Building regulations are now loosening up in Canada, reflecting the recent successes of the country’s wood use. Last month, Ontario raised the cap on timber structures from four storeys to six, just as British Columbia did in 2009.

But perhaps the most promising realisation of wood’s worth is in New Zealand, where the violent earthquakes of 2010 and 2011 left almost one third of the Christchurch’s buildings – including 220 heritage sites – up for demolition. Almost four years on, the city’s grand rebuild has begun, and wood has taken a step into the spotlight due to its durability in high-seismic activity zones. The “new” Christchurch, as outlined in the Central Recovery Plan, is proposed to be a low-rise, “greener, more attractive” city costing around NZ$40bn (£19bn), almost 20% of the country’s annual GDP.

A detail of the Merritt building in Christchurch’s central business district Photograph: PR

Andrew Buchanan, professor of timber design at the University of Canterbury, sees a growing interest in the use of wood in Christchurch’s rebuild. “When it first happened, people were scared of concrete and masonry buildings,” he says. “Wood was seen as a very desirable and very safe alternative.”

Earlier this year, Christchurch welcomed its first post-earthquake, multistorey timber structure – the Merritt building in the city’s central business district. The structure uses a “post-tension” technology – the brainchild of Buchanan and his colleagues – where timber is lashed together with steel tendons that act like rubber bands, allowing the building to snap back into place following any seismic movement. And recently, the Southern Hemisphere’s first engineered timber factory opened up in Nelson, producing timber panels for flat-pack cities across the globe.

In China, Arup is currently working to educate engineers on the use of wood. With even a superfirm like SOM – the architects behind One World Trade Centerand the Burj Khalifa – considering using of wood for high-rise construction, the industry finally appears ready to grasp its full potential.

Several of SOM’s buildings are in Chinese cities (the 71-storey Pearl River Building in Guangzhou, and the 88-storey Jin Mao in Shanghai, for example), so perhaps their Timber Tower could take root there too? “Judging from the speed that the Chinese usually adopt new technologies,” says Arup director Tristram Carfrae, “this really won’t take very long!”

This article was amended on Monday 6 October 2014. The NMIT arts and media building is in Nelson, not Christchurch