Seeder making its mark in Washington D.C.

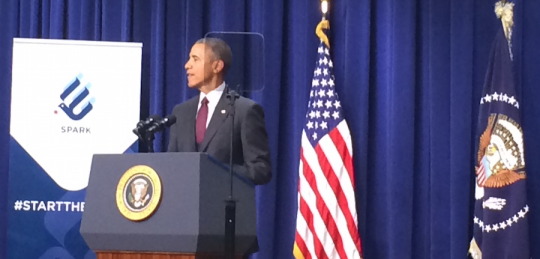

It was an eventful month for Seeder in Washington D.C. Seeder CEO Alex Shoer was invited to the White House as “Emerging Global Entrepreneur,” pitched on stage at the 1776 Challenge Finals to compete for $500k and spoke at the U.S.-China Renewable Energy Industries Forum to leaders in the energy industry and a large Chinese delegation about Seeder’s innovative business model on roof-top solar financing and how they are helping to deploy solar at scale in China.

Seeder had access to high level stake holders at the various events, including some of the biggest CEOs in the country (Brian Chesky – Airbnb, Julie Hanna -Kiva, Mark Cuban – Shark Tank, Steve Blank – Father of Lean Startup) plus high level officials at the Department of Energy, IFC/World Bank, Commerce department, and the US Export-Import bank.

Seeder officially launched their innovative zero-cost solar model for the China market in partnership with UGE earlier this year and it has been talked about in the press with articles in the Global Times and Wall Street Journal and taking off amongst commercial buildings in China, being deployed on over 2MW of projects.

If you want to learn more about how to get solar on your roof at no cost and lock in 10-15% energy savings from day one then fill out our solar request form here and we will get back to you within 24 – 48 hours.

Below are some of the events Alex Shoer attended and people he visited during his whirlwind trip in the D.C.

Now back in Shanghai, the plans including wrapping up their Angel funding round, closing a few new solar projects and identifying additional financing partners who want to invest in this high-reward solar deployment model.

To the next steps…